All Posts (6434)

A CELEBRATION OF LIFE FOR

JAMES NAKAPAAHU

Join us on

Saturday

Sept. 26

Noon – 4 pm

Nuuanu Valley Park

[just above Queen Emma’s Summer Palace]

bring chairs and mats

set up tables to gather petitions

and/or share information

come talk story with each other

while we celebrate the life of

a brother in the struggle

for more info, email palolo@hawaii.rr.com

or call 284-3460

SALES and MARKETING!LEARN HOW TO KILL FOR CORPORATE GREED, ILLEGALLY OCCUPY OTHER NATIONS AND COUNTRIES AND RAPE THEIR RESOURCES, HIDE BEHIND AND TWIST THE WORD "FREEDOM", TO MEAN: "YOUR FREEDOM TO TAKE AWAY THEIRS!" LEARN HOW SLAUGHTERING BABIES, SISTERS, BROTHERS, MOTHERS AND FATHERS IS A GOOD WAY TO CONTROL THE HOMELESS!YES LEARN IT ALL HERE IN " HAWAI'I", AMERICA'S TROPHY, HIDDEN BEHIND A 50TH STAR.

SALES and MARKETING!LEARN HOW TO KILL FOR CORPORATE GREED, ILLEGALLY OCCUPY OTHER NATIONS AND COUNTRIES AND RAPE THEIR RESOURCES, HIDE BEHIND AND TWIST THE WORD "FREEDOM", TO MEAN: "YOUR FREEDOM TO TAKE AWAY THEIRS!" LEARN HOW SLAUGHTERING BABIES, SISTERS, BROTHERS, MOTHERS AND FATHERS IS A GOOD WAY TO CONTROL THE HOMELESS!YES LEARN IT ALL HERE IN " HAWAI'I", AMERICA'S TROPHY, HIDDEN BEHIND A 50TH STAR.

September 18, 2009

Advertiser Staff

This morning, students from schools from Kailua toEwa were in awe as they were allowed to sit in the pilot's seat in afueling tanker, looking at the vast array of dials and levers. Theywere told by a pilot of an F-15 the specs: It's called "The Eagle," itcarries eight missiles, cost $15 million and has a machine gun on theright side of the aircraft.

"It's awesome," said Noah Au Young, aMomilani sixth-grader. "It can shoot 950 bullets in a couple ofseconds. I've seen one of these before."

Parking is available on base, but residents are being askedto not bring coolers, backpacks or duffle bags, chairs, weapons,alcohol or drugs on base. Fanny packs and purses, food and snacks willbe allowed on base. For more information go to wwww.hafb2009openhouse.com.

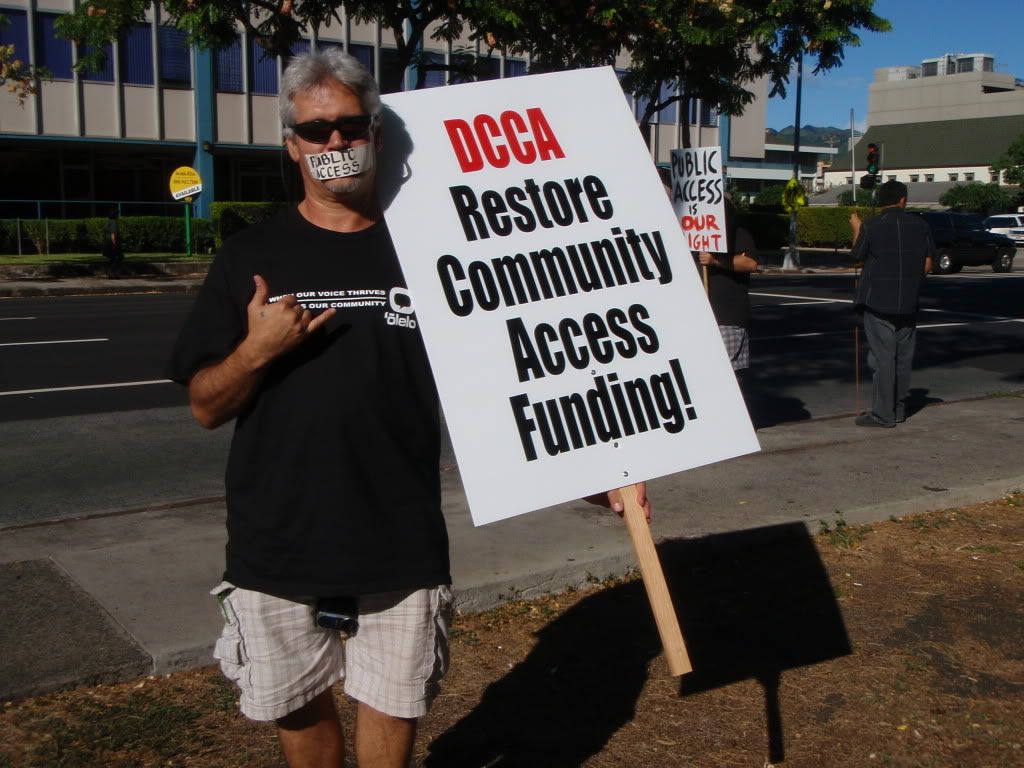

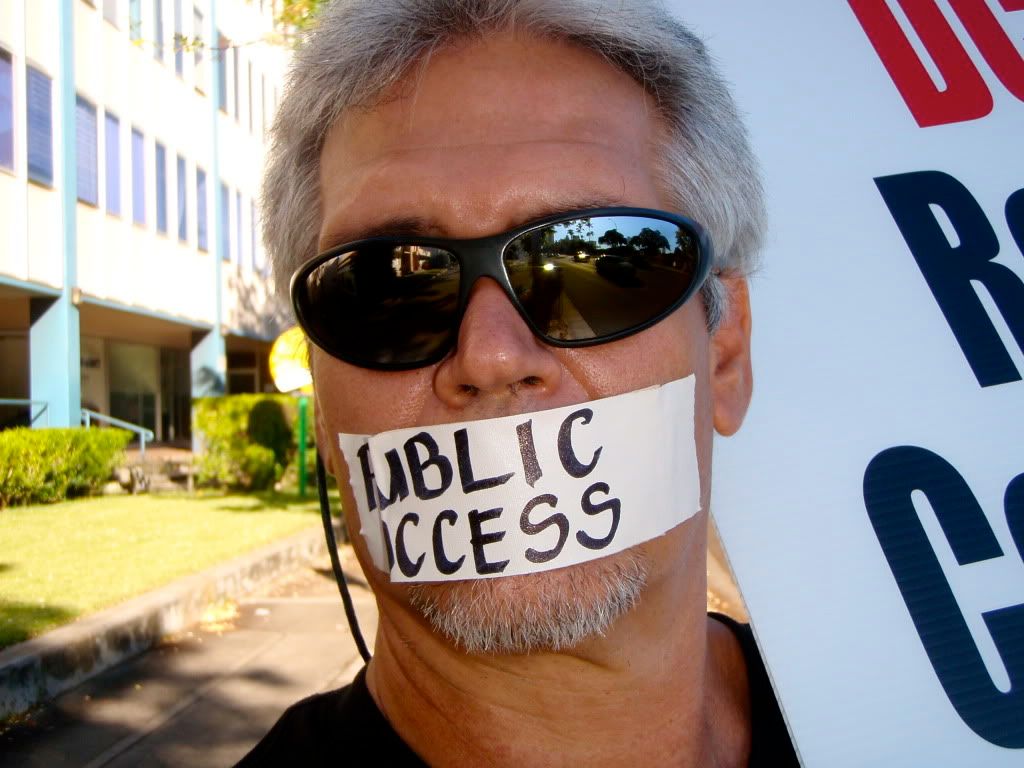

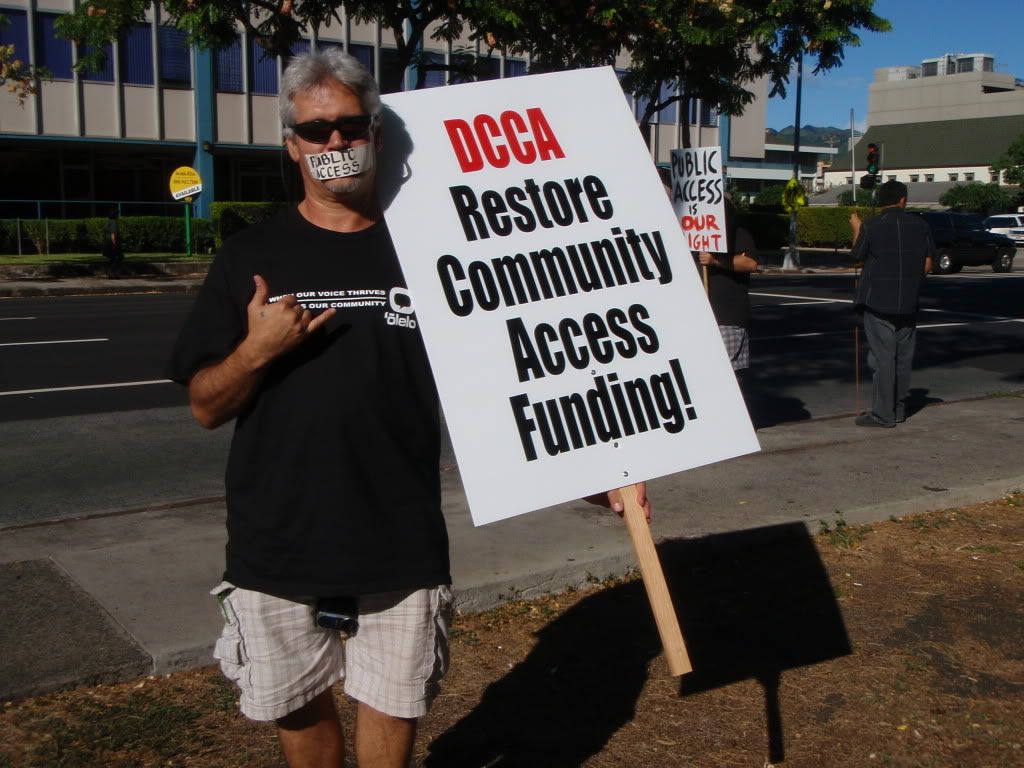

How the state's secret deal with AOL/Time Warner and Oceanic imperils the future of public access TV inHawai‘i.

The unexpected dose of corporatewelfare was buried in the state’s lengthy review and approval of the $350billion merger of Internet pioneer America Online with the entertainment andmedia conglomerate Time Warner, which could not be finalized until it got anofficial blessing in each community where the company owned cable systems,including Hawai‘i.

At that time, Oceanic was thesole cable provider on O‘ahu, the Big Island and Maui County. It established astatewide monopoly last year when, with little fanfare, it took over Garden IsleTelecommunications on Kaua‘i, the last independent cable provider in the state.Now if you want or need cable anywhere in the state, from Ka‘ü to Hanalei,Oceanic is your only option.

Regulators had onlylimited discretion in dealing with the AOL-Time Warner merger, but in some partsof the country the occasion was used to try to leverage additional publicbenefits from the cable company. Few succeeded, but here in Hawai‘i stateregulators went in the opposite direction, apparently paying tribute to AOL-TimeWarner’s political clout.

Decision and Order No. 261was signed by then-director of the Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs(DCCA), Kathryn Matayoshi, on Aug. 11, 2000. It slashed the number of cablechannels Oceanic is required to set aside for future public, education andgovernment use (known as PEG access channels), and at the same time changed akey formula that essentially lowered the rent Oceanic pays to string its cablesalong publicly owned rights-of-way.

For example,Oceanic had previously been required to devote up to 10 percent of availablechannels for PEG access on O‘ahu, but Matayoshi’s order reduced that to justfive channels, the number of channels already being utilized. Although notconsidered an absolute cap, it makes future expansion for public access channelsmore difficult to justify. With Oceanic now bragging about delivering 220digital channels, the reduction from the former 10 percent standard takes onadditional significance. Although putting a value on the lost channel capacityis difficult, knowledgeable observers estimate the value of each channel atupwards of $500,000 annually.

Those directly andimmediately affected by the cuts in Oceanic’s fees include the public access orcommunity media centers on each island. Cable fees also go to PBS Hawaii’s KHET,to an educational consortium that includes the University of Hawai‘i and theDepartment of Education, and to support an electronic network tying togetherschools and public buildings statewide, allowing for teleconferencing and otherdata services. The DCCA’s Cable Television Division itself retains a share ofthe fees to pay the costs of regulation.

Those whofollowed the process closely were stunned when the changes were discovered.Although a series of public hearings was held across the state to solicitcomments on the merger, there was no public notice that any giveaways of thiskind were even being considered.

“It came as a veryunpleasant surprise,” said Lurline McGregor, president and CEO of ‘ÖleloCommunity Television, Hawai‘i’s largest public access provider and one of thelargest in the nation.

“I first learned of it whenI read the signed D&O, after it was a done deal,” McGregor said. “We werenot given an opportunity to comment. Had I known this was in the works, believeme, I would have.”

Sean McLaughlin, director ofAkakü, the nonprofit group that operates Maui’s community access stations, wasalso caught by surprise.

“As a practical matter, wedidn’t find out until our check was reduced,” McLaughlin said. “We received nodirect notice.”

Dirk Koning, director of theCommunity Media Center in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and president of theWashington, D.C.-based Alliance for Communications Democracy, a legal defensefund supporting access centers across the country, told the Weekly that hedoesn’t know of any other place where a local community voluntarily gave upfunds or future channel capacity during the AOL-Time Warner mergerprocess.

In a world where global access toinformation and entertainment is controlled by fewer than 10 mega-corporations,the merged company took its place as the world’s largest media company,according to Advertising Age magazine.

Although cable regulators defend the changes in franchise terms, they have little comment on the secrecy with whichthe decisions were made, feeding the perception that state policies are undulyinfluenced by backroom deals between cable regulators and the industry they aresupposed to regulate.

It wasn’t simply that thepublic didn’t figure out what was going on until it was too late. The recordseems to show the issues were systematically hidden in order to eliminate anyopportunity for public questioning or debate.

Addingto the perception of backroom deals was the disclosure that Pamela Sonobe, wifeof Cable Division Administrator Clyde Sonobe, began working for anotherTime-Warner company in 2001, just a year after the merger was approved and asOceanic was preparing to establish its statewidemonopoly.

In September 2002, the CommunityTelevision Producers Association filed a complaint with the State EthicsCommission, alleging that Pamela Sonobe’s job with Time WarnerTelecommunications in Honolulu created a conflict of interest for her husband inhis oversight of Oceanic, another Time Warner company. The complaint cited anethics provision that prohibits any state employee from taking any officialaction directly affecting a business “in which he has a substantial financialinterest. …”

The Ethics Commission agreed thatSonobe’s employment gave her husband “a substantial financial interest” in TimeWarner Telecommunications. But the commission concluded it was not a conflict ofinterest. The commission’s ruling is contained in a Nov. 20, 2002, letter, acopy of which was provided to the Weekly by current DCCA Director MarkRecktenwald.

According to the commission’s findings,the cable and telecommunications firms are separate and distinct subsidiaries ofAOL-Time Warner with separate offices and no shared officers. Further, thecommission determined Clyde Sonobe’s cable duties do not require him to take anyaction “directly” affecting his wife’s employer.

“Wehave not been presented with any evidence that any specific action you take asthe Cable Television Administrator directly affects Time Warner Communications,”the commission concluded, a finding that is unlikely to give access advocatesmuch comfort.

However, in a March 11, 2003, letterto the Ethics Commission, Recktenwald disclosed that the Cable Division and TimeWarner Telecommunications are parties in a pending Public Utilities Commissionproceeding involving the state’s communications infrastructure. According toRecktenwald’s letter, the Cable Division has not “actively” participated in thecase since Clyde Sonobe took his post in 1995.

Forpurposes of the ethics law, however, “official action” is defined as “adecision, recommendation, approval, disapproval, or other action, includinginaction, which involves the use of discretionary authority.” As a result, eventhe decision not to participate actively in the PUC case could raise additionalethics concerns, and the matter is again being reviewed by the EthicsCommission.

Clyde Sonobe declined to discuss theconflict of interest charges with Honolulu Weekly except to refer to thecommission’s November letter, but did defend his role in handling the AOL-TimeWarner merger hearings.

“There were public hearingsgiving the community opportunity to voice whatever concerns they would have onthis change of ownership,” Sonobe said, referring to hearings held on eachisland except Kaua‘i during April and May 2000.

Butrecords show Oceanic did not request changes in the franchise agreement and gavethe public no warning of other issues that were ultimatelyaddressed.

“Time Warner Entertainment [the corporatesubsidiary that controls cable operations] will continue to honor its existingcontract with the state which is embodied in cable franchise,” Honolulu attorneyJohn Komeiji stated in testimony on behalf of the cable company. The company’scommitment to the franchise’s existing terms “will not be affected by AOL-TimeWarner merger in any way,” he said.

Reminded ofOceanic’s public position, Sonobe backpedaled.

“Ican’t answer specifically if these items were offered for public comment ornot,” Sonobe said. “I can’t remember. It may be the public was not aware ofthem.”

Former DCCA Director Matayoshi was unable toexplain how issues of channel capacity and franchise fee payments entered intothe proceedings if they were not in AOL-Time Warner’s application and did notcome up during the hearings.

“I just actually don’trecall,” Matayoshi said.

One group that should havehad a hand in the process is the Cable Advisory Committee, established by statelaw to offer advice to cable regulators.

In makingdecisions on cable franchise matters, the DCCA director is legally required toconsider any objections raised by the advisory committee. But the committee waseffectively eliminated by then-Gov. Ben Cayetano, who took office in 1994 andrefused to appoint any members to the committee. As terms of existing membersexpired, they were not replaced.

Akakü’s McLaughlinwas the last official member of the Cable Advisory Committee. His term expiredon June 30, 1996.

“It was never formally disbanded,”McLaughlin says of the committee. “It just sort of fadedaway.”

McLaughlin said he occasionally contactedCable Division staff before his term expired.

“Iwould call and ask, what’s going on? Any meetings?”

“They would tell me, ‘We don’t need your advice,’” McLaughlinsaid.

The public access movement dates back to the 1970s and ’80s, when federal law recognized the importance of the publicstake in alternatives to commercial television. As television became thedominant source of news and community understanding of public issues, lawmakersrealized the public has to be provided a way to participate in what is otherwisea prohibitively expensive medium, just as leaflets and pamphlets gaveindividuals or groups a way to express themselves inprint.

As a result, federal law gave communities theright to demand cable companies pay a fee and set aside channels for public,education and government programs. In order to avoid First Amendment issues thatwould quickly arise if local governments directly controlled these programs,they are administered by separate nonprofit organizations designed by cableregulators and funded by franchise fees.

‘Ölelo,O‘ahu’s access provider (broadcast on Oceanic Channels 52-56), was incorporatedin 1989, and others followed — Akakü on Maui, Na Leo ‘O Hawai‘i on the BigIsland, and Ho‘ike on Kaua‘i. All offer free or low-cost training in televisionproduction, support for individuals and groups that want to produce their owntelevision programs, and several channels to reach thepublic.

In the midst of the increasingly vociferousnational debate over the concentration of media ownership and control in fewerand fewer corporate hands, public access or community television has become aprimary battleground where free speech advocates confront corporate dominationof the airwaves.

“Public access cable is the onlyplace where the average, ordinary person can take the podium and have a voice,”said Richard Turner, a longtime advocate for community media and state policycoordinator for the Washington, D.C.-based Alliance for CommunityMedia.

“The whole principle underlying the FirstAmendment is that the people have a right to speak, but if it weren’t for publicaccess, this would no longer be possible in this electronic age,” Turnersaid.

Public access provides the only broadcastchannels without prior restraint, according to Akakü’s McLaughlin. “Any othercommercial or public channel would have to pre-screen and pre-approve everythingthat gets on the air.”

The upside, McLaughlin said,is that some very good programs are produced about local community issues andpublic affairs that would otherwise not exist. On the neighbor islands, wherethere are no locally originated commercial television stations, public accessprovides the only available local televisionprogramming.

The down side is sometimes unevenquality.

“We provide unfluoridated public speech,”McLaughlin said with a laugh. “No chlorine, no fluoride, and its got otherimperfections.

“With every other channel, whethercommercial or public, you don’t know what’s been taken out or put in by hiddeninterests,” McLaughlin said. “We deliver itunfiltered.”

Public access television has grown in sophistication and influence since ‘Ölelo was formed in 1989, providing a wayfor groups outside of the political establishment to make their views known andto impact public policy. It is not a contribution that is universallyappreciated.

Michael Edwards, an independent accessproducer on Kaua‘i, said he ran afoul of corporate interests when he begandocumenting the debate over the proposed sale of the island’s electric utilityand creation of a utility co-op several years ago.

Edwards said Kauai Electric officials first tried to block him from videotapingpublic meetings where the utility discussed its plans. Later, after Edwardscompleted a show and scheduled it for showing on Ho‘ike’s public access channel,the program was suddenly pulled from the schedule in the face of pressure fromthe utility. Although the program was later rescheduled, it did not appear atthe announced times, reducing its potentialaudience.

“It was a sad commentary for me thatpublic access would just roll over and give into censorship like that without somuch as a whimper,” Edwards said.

Sean McLaughlin onMaui tells a tale of arranging a lunch meeting with an island business leaderwho he hoped would help underwrite Akakü’s broadcast of a series of candidateforums during last year’s election campaign.

BeforeMcLaughlin could make his pitch, the developerinterrupted.

“He says, ‘Before we get started, letme just tell you I hate Akakü,’” McLaughlin recalled. “‘You guys use publicfunds to give a voice to people who misrepresent my projects. If I could, Iwould shut you down, I would put you out of business because you are giving avoice to irresponsible people.’”

McLaughlin said heoffered a standard response — that the answer to irresponsible speech is evenmore responsible speech rather than censorship.

Butthe businessman responded: “Sean, I can buy that [favorable programming]. I don’t need you for that. I need you to not let those people on yourstation.”

Akakü did not give in, and it isn’t clearfrom McLaughlin’s telling whether his developer friend ever seriously pushed hisattempt to silence critics. But it’s a clear warning of the pressures facingaccess providers.

Open access is also threatened byan internal dynamic, what Dirk Koning calls “the PBS-ing” of public access andcommunity television.

“The original kind of activistmovement that public access grew out of is losing some steam,” Koning observed.Whereas the original mandate was not to produce programming but to enable othersto produce their own programming on a first-come, first-serve basis, many accessorganizations are being reshaped into PBS-style productioncompanies.

There has traditionally been a basic philosophical difference between public television and public access television,although both started from similar motivations. Public television says: “Supportus and we will provide you programming that we select and control, and that wethink will be beneficial.”

Public access, on theother hand says: “Support us, and we’ll take those resources and provide a freeplatform and production resources so that anyone can produce television programsthat reflect their point of view.”

One vision iselitist, the other grassroots. Although not necessarily mutually exclusive,there is a clear tension between the two approaches.

As a result, ‘Ölelo has drawn heavy criticism from a group of access users forits increasing readiness to use its resources to produce and air professionalquality programs, which critics say compete unfairly with volunteer efforts.They say ‘Ölelo fails to assure that all have fair and equitable access toresources, including equipment, studio use, air time, production assistance andpromotional resources.

Lurline McGregor saysin-house productions take advantage of ‘Ölelo’s underutilized resources but donot crowd out other access users. Although she rejects the view that ‘Ölelo isshifting its emphasis, she also articulates the reasons for pursuing preciselysuch a path.

“When public access started out, it wasas a facilitator, but I’ll tell you, it hasn’t panned out,” McGregor said. “Onthe Mainland, communities are anxious to get rid of it because you don’t wantthat stuff in your living room.”

McGregor saysHawai‘i has largely been spared offensive programs like those seen in someMainland cities.

“We don’t have Nazi programs, hateprograms, or the penis-piercing programs,” she said. “But we are the place wherethe disenfranchised have a voice.”

“Look,” McGregorsaid, “everybody pays for access, but less than 1 percent of the community evercomes down and actively participates. What about the other 99percent?”

‘Ölelo, in McGregor’s view, has stayed astep ahead by assessing the community and attempting to serve up qualityprograms that match viewers’ perceived interests. Sometimes that can be done byproviding training and resources, or steering volunteers towards particularproductions. In other cases ‘Ölelo responds by taking over fullresponsibility.

“I really make no apologies for thein-house productions we do,” McGregor said. “We’re not a production house, butif there is a hot event, and we deem it will be beneficial to the community, wewill send our staff. But we don’t want to let an opportunity go by just becausewe can’t get volunteers.

“We’re not exactly changingthe paradigm, but expanding it,” she said. “We’ve got to do something to getcommunity support. If we don’t, the community is not going to give a damn if wewent away.”

Although ‘Ölelo remains committed toexpanding its core of active users, McGregor dismissed calls for more internaldemocracy in ‘Ölelo’s governance, including more representation of active accessusers on its board of directors.

“It’s kind of likethe food bank,” she said. “It’s not like foodless people are voting for membersof their board. You want people who will bring in differentqualities.”

But Richard Turner warns that pursuingboth production and access requires a very delicate balance that is difficult tomaintain.

“It’s a slippery slope,” Turner said.“When access providers become producers, there are unintended consequences.There’s a tendency to play more towards some opinions than others. And who’scontrolling the message? Is it a staff member or a communitygroup?”

“On the practical side, people who arevolunteering long hours to produce access programs feel disenfranchised when theaccess organization puts its staff and financial resources into producing itsown programs, with the natural tendency to devote advertising and promotionalresources to be sure those programs are watched. Individual producers begin tofeel disenfranchised, and wonder why they can’t get comparabletreatment.”

The three years since the merger have not been kind to AOL-Time Warner. The company’s total market value has plungedby more than 80 percent, falling from an estimated $350 billion at the time ofthe merger to just $55 billion today. Company Chair Steve Case, architect of themerger, was forced to resign.

Any hopes that reducedfranchise fees might translate into lower consumer prices were quickly dashedwhen Oceanic raised its rates almost immediately, leaving consumers paying asmuch as before. And the company has continued to raise rates, with another roundjust announced for O‘ahu consumers.

But OceanicPresident Nate Smith said rates have actually increased at a slower pace thanthe company’s costs of providing programming, and “our charge to consumersremains one of the lowest in the country.”

At thesame time, Oceanic has retained its reputation for providing cutting-edge cableservices, while investing millions in rebuilding and upgrading its neighborisland cable systems.

“With Time Warner owning themall, we’re able to bring the same quality of service enjoyed on O‘ahu to Kaua‘i,Maui and the Big Island,” Smith said.

Meanwhile,access advocates took their case to the Legislature again this year, withunsuccessful attempts to get a legislative audit of access providers and torequire them to comply with state open meetings and recordslaws.

Cable watchers are waiting to see whenGovernor Linda Lingle will move to shake up the DCCA Cable Television Division.Both during the campaign and after the election, Lingle has publicly called forshifting power over cable issues to the counties.

Anextreme move might be to transfer all regulatory powers to the local level,where cable decisions are made in many parts of the Mainland. A less ambitiousplan might aim to spread PEG resources more evenly among the counties, althoughthat would mean further reductions in funds available to‘Ölelo.

An immediately useful step would be tosimply appoint new members to the Cable Advisory Committee, which is stillauthorized by law, a quick way to reestablish a degree of public accountabilityto the cable regulation process.

Cable Television Division

Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs

P.O. Box 541

Honolulu, Hawaii 96809

Keali’i Lopez

Honolulu Weekly on DCCA, 2003Honolulu Weekly on DCCA, 2003

Honolulu Weekly on DCCA, 2003Honolulu Weekly on DCCA, 2003

UNLOCKING JUSTICE

Protecting Communities & Saving Money

Saturday, October 17, 2009

8:00 AM – 5:00 PM

Ching Conference Center

Chaminade University

3140 Waialae Avenue, Honolulu HI

Suggested donation is $15.00 to cover conference materials and meals.

Scholarships available to students. Parking is free.

Times are hard. Money is tight. Crime continues on a downward trend.

Most of Hawai`i’s incarcerated population is projected to

be classified as minimum or community custody –

the least restrictive of all custody levels.

Yet prisons continue to use up precious resources.

Join us to learn about new research, data & alternatives

proven to protect communities, save money, and strengthen families.

NOW is THE TIME FOR SMART JUSTICE

For more information, contact Community Alliance on Prisons – (808) 533-3454; kat.caphi@gmail.com

Sponsored by Chaminade University’s Alpha Phi Sigma – Criminology and Criminal Justice Department,

Community Alliance on Prisons, Drug Policy Forum of Hawai`i, Ka Lei Maile Ali`i Hawaiian Civic Club,

League of Women Voters

Mahalo to Hawai`i People’s Fund, Hawai`i Community Foundation, & the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation

For their generous support

Cable Television Division

Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs

P.O. Box 541

Honolulu, Hawaii 96809

Keali’i Lopez

For my family and friends who like KNOW:

Some of y'all asked me how the toy sharks (that I have in my office and in my bags) look. Yes... exciting! LOL I carry them everywhere and while some people immediately tell me that it is my aumakua, that was not the motivation for me to buy them from the Dollar Store. It was because for my work I work in a shark tank LOL Actually I told my husband that I HAD to get some toy sharks.Things happen for a reason.My office at home is in my reading room. I have two computers in my reading room... and one in my livingroom which is what my husband wanted but I did not want LOL Well the two that are in my reading room/office is set up so that one is for me and one is for my husband. My husband's desktop is right behind me. Sometimes my husband helps me with my work. I set up a system. He helps me on Sundays, Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.Well here is a crappy pic of one of the toy sharks that I have that I took with my Blackberry: Isle inmates' plight spurs tighter securityMale guards at a Kentucky prison have been accused of sexual misconduct

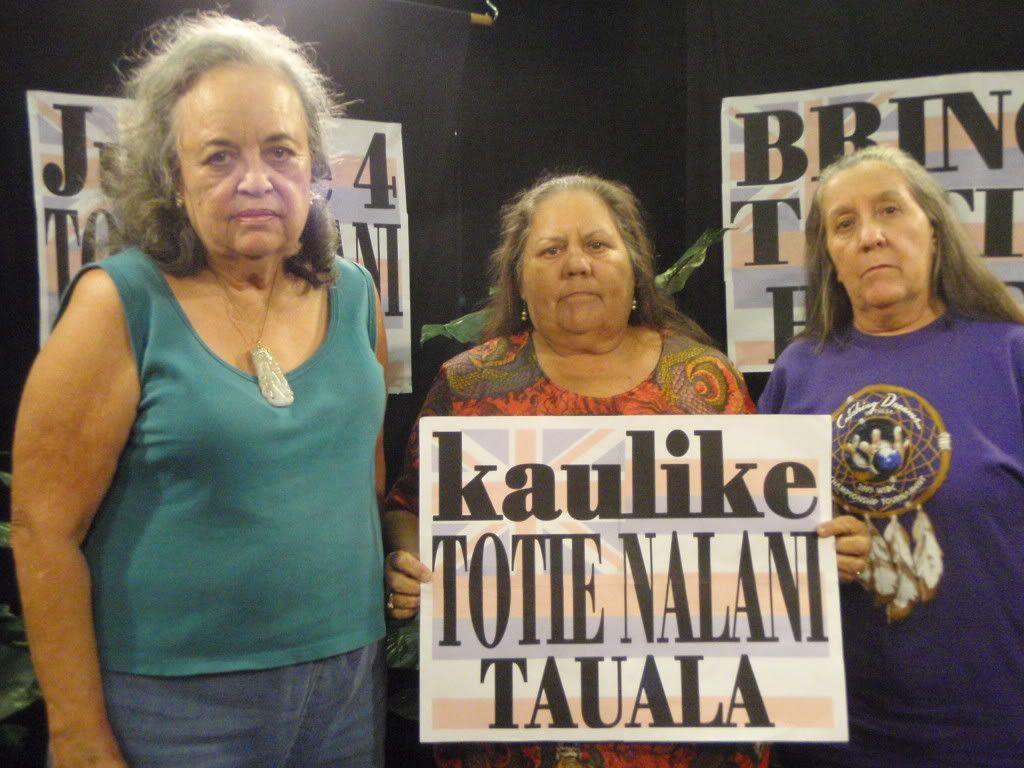

Isle inmates' plight spurs tighter securityMale guards at a Kentucky prison have been accused of sexual misconductWHEELWRIGHT, Ky. » Investigators from the Kentucky Department of Corrections called for security improvements at a private Appalachian women's prison to protect inmates from being sexually assaulted by male guards.

State investigators looked into the handling of 18 alleged cases of sexual misconduct by guards in the past three years at the Otter Creek Correctional Complex in this tiny coal town some 150 miles southeast of Lexington. Investigators made 14 recommendations to protect the more than 400 female inmates, including basic strategies like assigning female guards to supervise the women in their sleeping quarters.

Department of Corrections spokeswoman Jennifer Brislin said yesterday that a two-month probe by her agency turned up seven new allegations of sexual misconduct that she said will be reviewed for possible criminal and administrative charges.

Perched on a mountainside above Wheelwright, the Otter Creek prison came under public scrutiny earlier this summer when female inmates from Hawaii complained that they had been the subject of sexual assaults by their male guards. Corrections officials in Hawaii recently removed 165 inmates from Otter Creek, citing safety concerns.

Steve Owen, spokesman for Corrections Corp. of America, said the Tennessee-based company fully cooperated with Kentucky's investigation.

"We have a zero-tolerance policy for that kind of conduct, and we're going to fully support full prosecution," he said.

The medium-security prison, surrounded by fences and razor wire, employs about 190 people in this hardscrabble town which is struggling from job losses in the coal industry. While some communities fight to keep prisons out, Wheelwright and other Appalachian towns have welcomed prisons in because of the jobs they create.

The Rev. John Rausch, head of the Catholic Committee of Appalachia, has voiced concern about the growing number of federal and state prisons that have been built in the mountain region in recent years. Rausch said inmates who are often shipped in from hundreds, even thousands of miles away are reduced to "the status of commodities" by using them for job creation.

Kentucky Corrections Commissioner LaDonna Thompson said finding enough women willing to work as corrections officers at Otter Creek has been difficult. That, she said, had resulted in male guards supervising female inmates in areas of the prison where female guards would be a better option.

Owen said his company has already taken steps to prevent sexual assaults in the prison, built on a flat spot carved out of a Floyd County mountainside. Those steps include the installation of video cameras that he said will be a deterrent to sexual misconduct and will help investigators determine future allegations' validity.

Investigators from the Department of Corrections recommended yesterday that security cameras be installed and that staffers be assigned to monitor the cameras. They also recommended that the company hire more female corrections officers, conduct a security assessment of all areas of the prison vulnerable to sexual assaults, and train all staffers on provisions of the Prison Rape Elimination Act.

Justice Cabinet Secretary J. Michael Brown said last week that the state will not renew a contract to house inmates at Otter Creek unless Corrections Corp. of America hires a female security chief and hires a security staff that is at least 40 percent female.

Brislin said sexual misconduct charges have been substantiated against only five corrections officers at Otter Creek since 2007.

"The rogue actions of a few bad apples has really led to a very unfortunate characterization of the entire work force at that institution," Owen said.