See It Here

See It Here

See It Here

See It Here

See It Here

See It Here

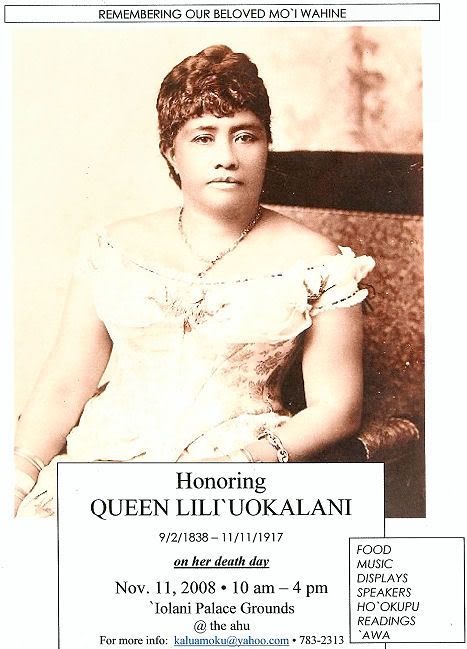

HonoringQUEEN LILI`UOKALANI9/2/1838 – 11/11/1917on her death dayNov. 11, 2008 • 10 am – 4 pm`Iolani Palace Grounds@ the ahuFor more info: kaluamoku@yahoo. com • 783-2313E komo mai!FOODMUSICDISPLAYSSPEAKERSHO`OKUPUREADINGS`AWA CEREMONYMea'ai: pua'a, char siu, pipi lahopipi, crispy moa, laiki palai, 'uala, poi, vegetables, roast pork, pastries, kulolo, juice, water a me 'awa.Queen Lydia Liliuokalani

HonoringQUEEN LILI`UOKALANI9/2/1838 – 11/11/1917on her death dayNov. 11, 2008 • 10 am – 4 pm`Iolani Palace Grounds@ the ahuFor more info: kaluamoku@yahoo. com • 783-2313E komo mai!FOODMUSICDISPLAYSSPEAKERSHO`OKUPUREADINGS`AWA CEREMONYMea'ai: pua'a, char siu, pipi lahopipi, crispy moa, laiki palai, 'uala, poi, vegetables, roast pork, pastries, kulolo, juice, water a me 'awa.Queen Lydia LiliuokalaniQueen Liliuokalani was the last reigning monarch of the Hawaiian islands. She felt her mission was to preserve the islands for their native residents. In 1898, Hawaii was annexed to the United States and Queen Liliuokalani was forced to give up her throne.

Queen Liliuokalani was deposed by the advocates of a Republic for Hawaii in 1893. She was born in Honolulu to high chief Kapaakea and the chiefess Keohokalole, the third of ten children. Her brother was King Kalakaua. Liliuokalanie was adopted at birth by Abner Paki and his wife Konia. At age 4, her adoptive parents enrolled her in the Royal School. There she became fluent in English and influenced by Congregational missionaries. She also became part of the royal circle attending Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma.

Liliuokalanie married a ha'ole, John Owen Dominis on September 16, 1862. Dominis would eventually serve the monarchy as the Governor of O'ahu and Maui. They had no children and according to her private papers and diaries, the marriage was not fulfilling. Dominis died shortly after she assumed the throne, and the queen never remarried.

Upon the death of her brother, King Kalakauam Liliuokalani ascended the throne of Hawaii in January 1891. One of her first acts was to recommend a new Hawaii constitution, as the "Bayonet Constitution" of 1887 limited the power of the monarch and political power of native Hawaiians. In 1890, the McKinley Tariff began to cause a recession in the islands by withdrew the safeguards ensuring a mainland market for Hawaiian sugar. American interests in Hawaii began to consider annexation for Hawaii to re-establish an economic competitive position for sugar. In 1893, Queen Liliuokalani sought to empower herself and Hawaiians through a new constitution which she herself had drawn up and now desired to promulgate as the new law of the land. It was Queen Liliuokalani's right as a sovereign to issue a new constitution through an edict from the throne. A group led by Sanford B. Dole sought to overthrow the institution of the monarchy. The American minister in Hawaii, John L. Stevens, called for troops to take control of Iolani Palace and various other governmental buildings. In 1894, the Queen, was deposed, the monarchy abrogated, and a provisional government was established which later became the Republic of Hawaii.

In 1893, James H. Blount, newly appointed American minister to Hawaii, arrived representing President Grover Cleveland. Blount listened to both sides, annexationists and restorationists, and concluded the Hawaiian people aligned with the Queen. Blount and Cleveland agreed the Queen should be restored. Blount's final report implicated the American minister Stevens in the illegal overthrow of Liliuokalani. Albert S. Willis, Cleveland's next American minister offered the crown back to the Queen on the condition she pardon and grant general amnesty to those who had dethroned her. She initially refused but soon she changed her mind and offered clemency. This delay compromised her political position and President Cleveland had released the entire issue of the Hawaiian revolution to Congress for debate. The annexationists promptly lobbied Congress against restoration of the monarchy. On July 4, 1894, the Republic of Hawaii with Sanford B. Dole as president was proclaimed. It was recognized immediately by the United States government.

In 1895, Liliuokalani was arrested and forced to reside in Iolani Palace after a cache of weapons was found in the gardens of her home in Washington Place. She denied knowing of the existence of this cache and was reportedly unaware of others' efforts to restore the royalty. In 1896, she was released and returned to her home at Washington Place where she lived for the next two decades. Hawaii was annexed to the United States through a joint resolution of the U. S. Congress in 1898 . The "ex-"queen died due to complications from a stroke in 1917. A statue of her was erected on the grounds of the State Capital in Honolulu.

Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) Chairperson Laura Thielen announced today that the state will not take any action to evict six Kahana Valley families who are living in Kahana Valley Park, while the 2009 Legislature considers revisions to the law to address this issue. “Although we could not resolve this issue with the six families, we are encouraged it will be addressed during the 2009 legislative session,” said Thielen. “We trust the Legislature will continue to respect the basic foundation of the public’s right to access state parks, keep residential areas separated from the public areas and make Kahana Valley a public park that welcomes and enriches all residents and visitors of Hawai’i.”

Some of the residents, such as Lena Soliven, had been promised leases by the state and had fulfilled legal and financial requirements to acquire those leases. However, an abrupt shift in state policy in March of this year pulled those leases out of reach.

The new policy was prescribed by Attorney General Mark Bennett in an opinion on Act 5, a law passed in 1987 that allowed the land board to issue residential leases in Kahana ahupua‘a. The land had been purchased by the state through eminent domain from a private estate in 1970. Kahana ahupua‘a is an important asset because it contains approximately 80% of the island’s water, and is the beginning of the Waiahole Ditch.

A grassroots victory

Soliven credited the community’s support for the successful stopping of the evictions.

“I truly believe that it was a combined effort,” she said.

More than 200 supporters came to Kahana ahupua‘a before the morning daybreak last Monday to prevent the anticipated eviction. Notices posted by state officers ordered residents to vacate their humble, makeshift homes by 6 am. By 5 am, the perimeter of Ahupua‘a o Kahana park was lined with young and old people from throughout the island, carrying signs and flags, calling for a stay on the evictions.

Next: the legislature

Attention now shifts to the legislative branch. State Sen. Clayton Hee (D-District 23), who won his re-election last night with 10,722 votes—beating his opponent, Republican Richard Fale, by a 2-to-1 margin—has promised to pursue a legislative resolution to the Kahana situation.

Hee and the state senate are on record supporting a new bill for Kahana ahupua‘a. The House of Representatives, by contrast, refused to pass Hee’s previous bills.

That may change in January, however. Attorney Jessica Wooley (D) beat incumbent Rep. Colleen Meyer (R) for the district representing Kahana ahupua‘a, which may make the Democratic Legislature more inclined to support taking action on the Kahana issue.