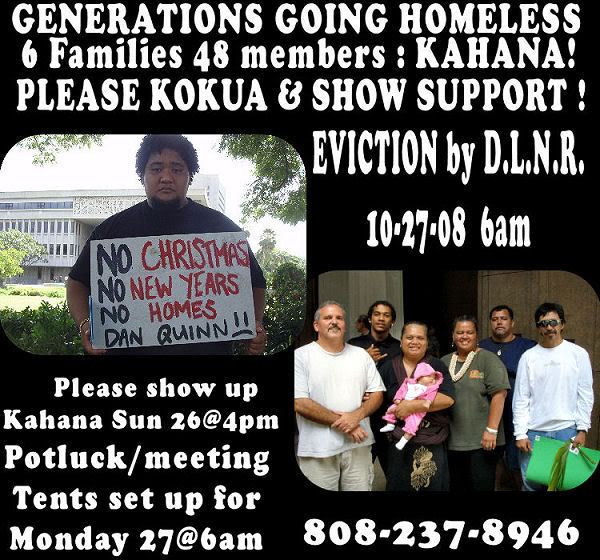

6 Kahana families 48 members to be evicted on 10-27-08 @ 6am this comming monday morning ! the Ohana's have asked family ,friends and "Supporters" to please come to KAHANA ,today10-26-08 4.pm We Will Have Tents Up for potluck /Meeting /Hold Signand PLEASE STAND WITH US MONDAY!Mahalo nui loa me ka ha'aha'aPonoPLEASE KOKUA !

6 Kahana families 48 members to be evicted on 10-27-08 @ 6am this comming monday morning ! the Ohana's have asked family ,friends and "Supporters" to please come to KAHANA ,today10-26-08 4.pm We Will Have Tents Up for potluck /Meeting /Hold Signand PLEASE STAND WITH US MONDAY!Mahalo nui loa me ka ha'aha'aPonoPLEASE KOKUA ! Here's some research on Kahana. I've attached a DLNR "facts" letter and notices of eviction. (DLNR sure has been busy...desecration of our iwi kupuna at Naue, depletion of East Maui water, harrasment of kanaka maoli families at Kaena, to Kahana evictions...what else is there?)Here is a HANA HOU article on Kahana that's good. It is followed by a State of Hawaii fact sheet.HANA HOUThe entire bayfront and valley, with only the most minimal intrusion of human habitation, is now owned by the state and managed as a 5,300-acre “living park” called Ahupua‘a ‘O Kahana, but the only signs of this are the parking lot and restrooms across the highway from the beach, tucked in under an old coconut grove that was planted circa 1909. A little ways up Kahana Valley Road is a down-at-the-heels “Orientation Center,” which, sign-less, is closed on a weekday morning. Further inland, the overgrown roadway opens onto a hillside clearing where the gardened plots of a handful of newish houses extend for a few hundred yards.The little subdivision was built after the state’s Department of Land and Natural Resources acquired the valley in 1969 in order to protect the most intact ahupua‘a left on O‘ahu from an ambitious development scheme. The state relocated most of the valley’s thirty-odd resident families (who were, for the most part, the Hawaiian descendants of the valley’s original farmers and fishermen) inland, to this mid-valley settlement. Since then, management of the valley has been an inconclusive tug-of-war between residents and bureaucrats, with little to recommend the well-intentioned transaction except for some measure of security and stability for residents, a few maintained hiking trails, a brochure—and a blissful peace and quiet.Near the new settlement’s entrance, a small trash fire crackles in the middle of a big empty lawn that slopes down to the road. A border of infant plumeria trees and ti plants encloses the plot. At the top of the lawn, at the edge of the forest, an elderly man sits in one of two lawn chairs, watching the smoke rise from his fire. The vacant chair next to the man seems like an invitation, so I walk up the lawn and introduce myself, telling him I’m writing a magazine article about the area. Friendly yet circumspect, he invites me to sit down.George DelaCerna, 72, was born in Kahana Valley, as was his Hawaiian mother. His father, of Spanish descent, was from Maui. A retired superintendent with the refuse division for the City and County of Honolulu (“Good pension!” he exclaims), he lives with his wife and grown daughter, one of seven children, in a substantial house next-door to the empty lot.We chat for awhile, about how he planted and tends this empty lawn though he doesn’t own it; about being stationed in Germany with the U.S. Army during the Korean War; and about the monthly meetings that the lease-holding residents of Kahana have with the state’s landlord bureaucrats.“My wife goes to the meetings,” George says, “but I’m not the type of person who sits in meetings and listens to all what they need to say, because I understand already what it’s all about. I don’t need to hear it again.”The lawn chairs offer a view of much of the valley’s floor and overgrown streambed where there were once abundant taro fields, wauke (paper mulberry), bananas, breadfruit and sweet potatoes. On the other side, the velvety ramparts of its east wall. Near the head of the valley, the dreamy, sculpted 2,265-foot peak of Pu‘u‘ohulehule punctuates the view.One of the wettest spots on O‘ahu, Kahana’s mauka sections absorb more than 250 inches of rain each year. During the first half of the twentieth century, sugar planters engineered an unprecedented network of tunnels and canals into the Ko‘olau mountain spine to capture an average of thirty million gallons of water per day and ship it to the sprawling sugarcane fields that covered the flat, dry leeward plains of O‘ahu like a giant lawn. The on-going water transfer (which now irrigates the thirsty suburbs that replaced the cane fields) has significantly reduced many windward stream flows, including Kahana.The mosquitoes begin to gather, and the conversation lags, so I prepare to take my leave and turn off my palm-sized digital recorder. But George signals that I should sit back down. He isn’t finished and wants to talk. The fire has subsided to glowing embers. I turn the recorder back on.“Actually, what we want, here in the valley, is we want our land back.” His voice firms up. “We don’t want to be controlled by the state the way they’re doing now. We did all right, back when this valley was private. We used to have farmers up here and taro patches, and it was beautiful. The people kept it clean. But then the state came in and said, ‘You can’t do this, you can’t own anything, you can only do this.’ They took the land away from us. They gave us no choice, so to speak. Who are they to do that? They don’t own the land to begin with. It’s ours; it belongs to us, the Hawaiian people.”State of HawaiiFACT SHEETKahana: What Was, What Is, What Can BeHighlightsThe State acquired the ahupua`a `o Kahana in 1969 from the estate of Mary Foster and six individual lessees. The State was prompted to do so by a 1965 report that portrayed Kahana as a blank slate to be developed in a highly commercial way, including 1,000 camping sites, hotel, cabins, restaurant, a botanical garden, a man-made lake, and shops. An additional factor supporting state acquisition was that it was one of the few, if not the only, ahupua`a left under virtually sole ownership and in a relatively pristine state.The families living in Kahana at that time had long-standing ties to the valley, and lobbied the Legislature to allow them to stay in the park and preserve their lifestyle. In 1970, a Governor's Task Force proposed the concept of a "living park," which would allow the residents to remain on the land and be a part of the park.To permit the Kahana residents to remain in the park, the State devised a scheme in which the lessee families would earn the right to a 65-year lease in the park by providing 25 hours of interpretive services per month to the park to preserve, restore, and share Kahana's history and rural lifestyle with the public.The State paid for a number of master plans for Kahana. Taking their tone from the original report, these were extremely ambitious and expensive, and would have involved removing the remaining families still living in Kahana. The community and the legislature rejected these plans. The Kahana residents proposed more modest plans that focused on the rural culture of the ahupua`a, but these were not accepted by the Department of Land and Natural Resources.The Bureau contacted twenty-four state, federal, and county agencies about their jurisdiction over or involvement with Kahana. The agencies fell into three categories: some of the agencies had no involvement in Kahana; some had regulatory powers over proposed changes to the ahupua`a but otherwise were not involved; and others had active jurisdiction over a portion of Kahana and could generate their own projects within their limited jurisdiction. It was agreed that the agency with primary jurisdiction is the Department of Land and Natural Resources' State Parks Division.Two management structures were examined. The first is one in which the management entity has control over the entity, similar to the Kaho`olawe Island Reserve Commission. In the other model, each government agency retains its current jurisdiction and the management entity serves as a coordinator between the agencies and as an ombudsman between the lessees and the agencies.However, discussion of the format of a management agency, whether the control or the coordinator model, and which specific entity should be that manager, is premature at this time as there is a crucial but missing element which must be done first: Kahana must have a master plan.A management entity will not be able to function efficiently and effectively, or be evaluated appropriately, without a master plan. A master plan for Kahana, co-authored by the Kahana lessees, is urgently needed before a change in management should be made. If an entire master plan is not financially feasible at this time, a specific phased plan could be started immediately to deal with the three most-pressing issues relating to Kahana. The first is community-building between the lessees, and between the lessees as a group and State Parks to address the friction that is blocking full participation by every involved person in making the ahupua`a `o Kahana a true living park. The second is a specific plan to address interpretive service and lease issues; and the third is development of a full set of goals for Kahana to use in directing interpretive service hours and in seeking assistance from other governmental agencies.Funding for a plan for Kahana, whether it be a full master plan or a more focused phased plan, should be among the Department of Land and Natural Resources' top priorities. However, a plan for Kahana will only be effective if the lessees, who are required to be the main source of staffing via their interpretive services, are co-architects of the plan.Until a master plan is in place, deciding who the management entity should be, or the scope of its powers, is premature.Anticipated QuestionsQ: What about Kahana makes it different from other state parks?A: Kahana differs from all other state parks as it is an intact ahupua`a – the basic ancient Hawaiian land division – and can demonstrate all of the resources – mountain, upland, shoreline, and ocean – that the ancient Hawaiians used for survival. Kahana is also unique in its "living park" arrangement with lessees whose ancestors have lived on the land and who can serve as the stewards of the land and interpreters of Kahana's rural culture.Q: Why should funding its master plan be a priority?A: The State took full possession of Kahana in 1969 and attempted several master plans in the ensuing decades. All the plans were rejected as they were too grandiose. Meanwhile, the kūpuna of Kahana, who suggested more modest but ignored plans that would have restored and displayed the traditional nature and culture of Kahana, are passing away. Also, the relationship between the lessees and State Parks has suffered due to the long delay in devising a master plan. Action is needed now to utilize the wisdom of the remaining kūpuna, support those lessees who are striving to restore Kahana, and encourage those who need guidance and motivation.

Here's some research on Kahana. I've attached a DLNR "facts" letter and notices of eviction. (DLNR sure has been busy...desecration of our iwi kupuna at Naue, depletion of East Maui water, harrasment of kanaka maoli families at Kaena, to Kahana evictions...what else is there?)Here is a HANA HOU article on Kahana that's good. It is followed by a State of Hawaii fact sheet.HANA HOUThe entire bayfront and valley, with only the most minimal intrusion of human habitation, is now owned by the state and managed as a 5,300-acre “living park” called Ahupua‘a ‘O Kahana, but the only signs of this are the parking lot and restrooms across the highway from the beach, tucked in under an old coconut grove that was planted circa 1909. A little ways up Kahana Valley Road is a down-at-the-heels “Orientation Center,” which, sign-less, is closed on a weekday morning. Further inland, the overgrown roadway opens onto a hillside clearing where the gardened plots of a handful of newish houses extend for a few hundred yards.The little subdivision was built after the state’s Department of Land and Natural Resources acquired the valley in 1969 in order to protect the most intact ahupua‘a left on O‘ahu from an ambitious development scheme. The state relocated most of the valley’s thirty-odd resident families (who were, for the most part, the Hawaiian descendants of the valley’s original farmers and fishermen) inland, to this mid-valley settlement. Since then, management of the valley has been an inconclusive tug-of-war between residents and bureaucrats, with little to recommend the well-intentioned transaction except for some measure of security and stability for residents, a few maintained hiking trails, a brochure—and a blissful peace and quiet.Near the new settlement’s entrance, a small trash fire crackles in the middle of a big empty lawn that slopes down to the road. A border of infant plumeria trees and ti plants encloses the plot. At the top of the lawn, at the edge of the forest, an elderly man sits in one of two lawn chairs, watching the smoke rise from his fire. The vacant chair next to the man seems like an invitation, so I walk up the lawn and introduce myself, telling him I’m writing a magazine article about the area. Friendly yet circumspect, he invites me to sit down.George DelaCerna, 72, was born in Kahana Valley, as was his Hawaiian mother. His father, of Spanish descent, was from Maui. A retired superintendent with the refuse division for the City and County of Honolulu (“Good pension!” he exclaims), he lives with his wife and grown daughter, one of seven children, in a substantial house next-door to the empty lot.We chat for awhile, about how he planted and tends this empty lawn though he doesn’t own it; about being stationed in Germany with the U.S. Army during the Korean War; and about the monthly meetings that the lease-holding residents of Kahana have with the state’s landlord bureaucrats.“My wife goes to the meetings,” George says, “but I’m not the type of person who sits in meetings and listens to all what they need to say, because I understand already what it’s all about. I don’t need to hear it again.”The lawn chairs offer a view of much of the valley’s floor and overgrown streambed where there were once abundant taro fields, wauke (paper mulberry), bananas, breadfruit and sweet potatoes. On the other side, the velvety ramparts of its east wall. Near the head of the valley, the dreamy, sculpted 2,265-foot peak of Pu‘u‘ohulehule punctuates the view.One of the wettest spots on O‘ahu, Kahana’s mauka sections absorb more than 250 inches of rain each year. During the first half of the twentieth century, sugar planters engineered an unprecedented network of tunnels and canals into the Ko‘olau mountain spine to capture an average of thirty million gallons of water per day and ship it to the sprawling sugarcane fields that covered the flat, dry leeward plains of O‘ahu like a giant lawn. The on-going water transfer (which now irrigates the thirsty suburbs that replaced the cane fields) has significantly reduced many windward stream flows, including Kahana.The mosquitoes begin to gather, and the conversation lags, so I prepare to take my leave and turn off my palm-sized digital recorder. But George signals that I should sit back down. He isn’t finished and wants to talk. The fire has subsided to glowing embers. I turn the recorder back on.“Actually, what we want, here in the valley, is we want our land back.” His voice firms up. “We don’t want to be controlled by the state the way they’re doing now. We did all right, back when this valley was private. We used to have farmers up here and taro patches, and it was beautiful. The people kept it clean. But then the state came in and said, ‘You can’t do this, you can’t own anything, you can only do this.’ They took the land away from us. They gave us no choice, so to speak. Who are they to do that? They don’t own the land to begin with. It’s ours; it belongs to us, the Hawaiian people.”State of HawaiiFACT SHEETKahana: What Was, What Is, What Can BeHighlightsThe State acquired the ahupua`a `o Kahana in 1969 from the estate of Mary Foster and six individual lessees. The State was prompted to do so by a 1965 report that portrayed Kahana as a blank slate to be developed in a highly commercial way, including 1,000 camping sites, hotel, cabins, restaurant, a botanical garden, a man-made lake, and shops. An additional factor supporting state acquisition was that it was one of the few, if not the only, ahupua`a left under virtually sole ownership and in a relatively pristine state.The families living in Kahana at that time had long-standing ties to the valley, and lobbied the Legislature to allow them to stay in the park and preserve their lifestyle. In 1970, a Governor's Task Force proposed the concept of a "living park," which would allow the residents to remain on the land and be a part of the park.To permit the Kahana residents to remain in the park, the State devised a scheme in which the lessee families would earn the right to a 65-year lease in the park by providing 25 hours of interpretive services per month to the park to preserve, restore, and share Kahana's history and rural lifestyle with the public.The State paid for a number of master plans for Kahana. Taking their tone from the original report, these were extremely ambitious and expensive, and would have involved removing the remaining families still living in Kahana. The community and the legislature rejected these plans. The Kahana residents proposed more modest plans that focused on the rural culture of the ahupua`a, but these were not accepted by the Department of Land and Natural Resources.The Bureau contacted twenty-four state, federal, and county agencies about their jurisdiction over or involvement with Kahana. The agencies fell into three categories: some of the agencies had no involvement in Kahana; some had regulatory powers over proposed changes to the ahupua`a but otherwise were not involved; and others had active jurisdiction over a portion of Kahana and could generate their own projects within their limited jurisdiction. It was agreed that the agency with primary jurisdiction is the Department of Land and Natural Resources' State Parks Division.Two management structures were examined. The first is one in which the management entity has control over the entity, similar to the Kaho`olawe Island Reserve Commission. In the other model, each government agency retains its current jurisdiction and the management entity serves as a coordinator between the agencies and as an ombudsman between the lessees and the agencies.However, discussion of the format of a management agency, whether the control or the coordinator model, and which specific entity should be that manager, is premature at this time as there is a crucial but missing element which must be done first: Kahana must have a master plan.A management entity will not be able to function efficiently and effectively, or be evaluated appropriately, without a master plan. A master plan for Kahana, co-authored by the Kahana lessees, is urgently needed before a change in management should be made. If an entire master plan is not financially feasible at this time, a specific phased plan could be started immediately to deal with the three most-pressing issues relating to Kahana. The first is community-building between the lessees, and between the lessees as a group and State Parks to address the friction that is blocking full participation by every involved person in making the ahupua`a `o Kahana a true living park. The second is a specific plan to address interpretive service and lease issues; and the third is development of a full set of goals for Kahana to use in directing interpretive service hours and in seeking assistance from other governmental agencies.Funding for a plan for Kahana, whether it be a full master plan or a more focused phased plan, should be among the Department of Land and Natural Resources' top priorities. However, a plan for Kahana will only be effective if the lessees, who are required to be the main source of staffing via their interpretive services, are co-architects of the plan.Until a master plan is in place, deciding who the management entity should be, or the scope of its powers, is premature.Anticipated QuestionsQ: What about Kahana makes it different from other state parks?A: Kahana differs from all other state parks as it is an intact ahupua`a – the basic ancient Hawaiian land division – and can demonstrate all of the resources – mountain, upland, shoreline, and ocean – that the ancient Hawaiians used for survival. Kahana is also unique in its "living park" arrangement with lessees whose ancestors have lived on the land and who can serve as the stewards of the land and interpreters of Kahana's rural culture.Q: Why should funding its master plan be a priority?A: The State took full possession of Kahana in 1969 and attempted several master plans in the ensuing decades. All the plans were rejected as they were too grandiose. Meanwhile, the kūpuna of Kahana, who suggested more modest but ignored plans that would have restored and displayed the traditional nature and culture of Kahana, are passing away. Also, the relationship between the lessees and State Parks has suffered due to the long delay in devising a master plan. Action is needed now to utilize the wisdom of the remaining kūpuna, support those lessees who are striving to restore Kahana, and encourage those who need guidance and motivation.State Evicting Some Residents From Kahana Valley Cultural Park

Residents say flawed laws hurting those with ancestral ties

KAHANA — After living in Kahana Valley for generations, families that once fought the state for the right to stay there — and won — now face eviction on Monday.

But after 30 years, the living cultural aspect of the park is being questioned and some who once were told they could have a lease are being pushed out. Residents said poor planning by the state Department of Land and Natural Resources and flawed laws are at fault.

Sunny Greer, a Kahana Valley resident who is not being evicted, said failure to comply with Western law and rules is forcing people out and creating a divide-and-conquer atmosphere.

"They want us out," Greer said. "They're picking on each and every one of us until there's not any one of us left. What hurts me is, that for which our ancestors a generation ago worked so hard for, the long-term leases, has now divided us. We're waiting for someone to default (in order to get their lease)."

Greer said the state is trying to use Western law to govern Hawaiian culture, and the two don't mix.

DLNR declined to comment but did provide a written statement about the eviction.

It said six families must leave the park because they do not have residential leases or permits to live there. A law that provided for long-term leases there expired in 1993 and no new leases can be issued, DLNR said. Final notice was posted Wednesday.

"This is in keeping with the public park purpose that would be impacted by an expanded residential subdivision in the park," said Laura H. Thielen, DLNR chairwoman. "With the enactment of Act 5 by the state Legislature in 1987, the state sought to accommodate families with ties to Kahana, but it was not the intent of the state or Legislature to provide housing for all those in future generations.

"If new lots were permitted, ultimately the park would be displaced by a subdivision. We are seeking a balance between the public's use of Kahana as a park with the desire of families to reside here," she said.

lacking a master plan

Many questioned the state's resolve in creating a living park for the public.

Greer said the key to the park's success is a master plan, but the state hasn't created one and did nothing with the one produced by residents in 1985.

"I don't think there was much thought or even much good-faith effort in fulfilling this living aspect of this cultural living park," she said. "There seems to be more emphases on parks and not the living aspect."

Four years ago, the state evicted a family from the shore of Kahana Bay saying it wanted to provide more park space, said Thoran Evans, who is being evicted. But the land is chained off, overgrown with weeds and a dumping ground for trash, Evans said.

DLNR operates the park piecemeal with inconsistent rules that don't seem to apply to everyone equally, he complained.

Evans had been trying to regain a family lease that was under his sister's name. She was unable to get financing and was behind in the number of hours she was required to work, he said. Apparently the state sent her a letter revoking her lease, but she never received it, he said. Evans said that when he called the state, he learned the letter was sitting on someone's desk, never opened.

"I don't understand why they took it away in the beginning," he said. "My family wasn't notified. If we were notified we were in trouble with the lease, we would do whatever is possible to get caught up."

Evans said his family has tried to meet the monthly work requirement but there are few activities to work on. Some families do maintenance to fulfill the requirement, but when his family asked for the same opportunity, it was denied, he said.

"I felt really discriminated against," Evans said. "Our family, no matter what we tried to do, we're just pushed aside for some reason."

Each family is being evicted for various reasons, said Ervin Kahala, who was told in 2000 that he would get a lease, but earlier this year learned that a new interpretation of the law forbids the state from issuing new leases even though he grew up in the valley and has ancestral ties to it.

"I'm not prejudiced but (the state) is using white man's law as an excuse," Kahala said.

Act 5 provisions

The law he referred to is Act 5, adopted by the state Legislature in 1987 that set up the living park concept and provided 31 leases to families who could prove they had a history there. DLNR took six years to finalize the leases but no provisions were made for extended family.

Kahala said he spent thousands of dollars preparing the land, acquiring blueprints and getting paperwork in order. He and Evans said they were both promised leases and there are leases available out of the original 31.

Some 30 people will be evicted, and some residents said their departure will create safety problems. They said many of those affected live in a flood plain in the lower valley where they are the eyes and ears of the community. They live near the entrance and make sure the grass is trimmed and children are visible to drivers.

Charmaine Kahala, Ervin Kahala's sister-in-law who lives in the valley but is not being evicted, said she sent a letter to the state asking it to reconsider its eviction. She predicted the grass would grow long, homeless people would move in, drugs would become an issue and state buildings in the lower section would be subject to vandalism.

"I'm not fighting the eviction," she said, but she wanted assurance that children would be safe. The state did not respond to her letter, she said.

Jessica Wooley, an attorney running as a Democrat for state representative in the 47th District, which includes Kahana, said she also wrote a letter asking the state to hold off on the evictions and to meet with her. Wooley said she had represented another family in the valley and helped them keep their lease.

"I'm sure that the families haven't been perfect, but the way that it's set up right now, it's not workable," she said. "The laws that were passed to deal with the land over there are old and they need to be revised.

"The state pushing forward with eviction right now shows a total lack of compassion and responsibility on the state's part."

Reach Eloise Aguiar at eaguiar@honoluluadvertiser.com.

Comments