This article discusses the forces and perceptions that played a role in the rebellion against the Superferry on Kaua'i. These same points apply to Maui.

This article discusses the forces and perceptions that played a role in the rebellion against the Superferry on Kaua'i. These same points apply to Maui.Hawai'i Business Newshttp://www.msplinks.com/MDFodHRwOi8vd3d3Lmhhd2FpaWJ1c2luZXNzLmNvbS9IYXdhaWktQnVzaW5lc3MvSnVuZS0yMDA4L1NvbWV0aGluZ3MtSGFwcGVuaW5nLUhlcmUvaW5kZXgucGhw'>http://www. hawaiibusiness. com/Hawaii-Business/June-2008/Somethings-Happening-Here/index. php

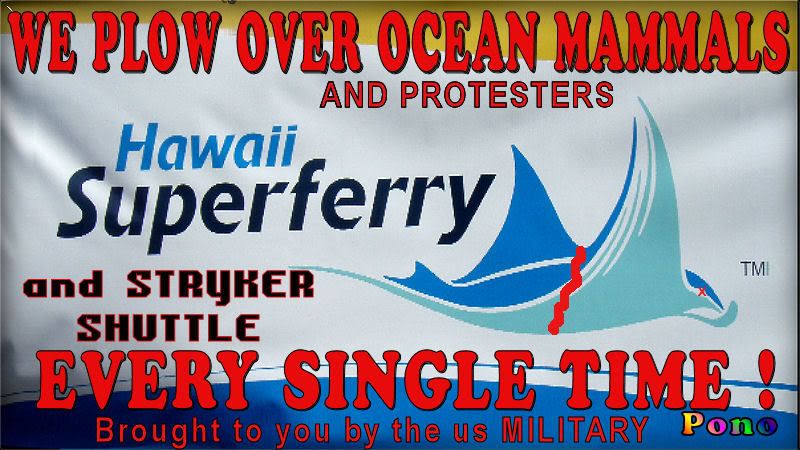

Everything went completely wrong. There was a lone surfer, straddling his maybe 9-foot surfboard, floating in Nawiliwili Harbor, arms raised, staring defiantly at the prow of the 350-foot, high-speed Alakai. The massive boat owned by the Hawaii Superferry venture was making its inaugural trip to Kauai last August and executives were trumpeting how it would make interisland travel cheaper and provide alternative avenues for businesses to send goods between the Islands.

Everything went completely wrong. There was a lone surfer, straddling his maybe 9-foot surfboard, floating in Nawiliwili Harbor, arms raised, staring defiantly at the prow of the 350-foot, high-speed Alakai. The massive boat owned by the Hawaii Superferry venture was making its inaugural trip to Kauai last August and executives were trumpeting how it would make interisland travel cheaper and provide alternative avenues for businesses to send goods between the Islands.But there was that surfer, caught in one of the most memorable news photographs in recent memory, staring down big business, protecting his island, risking his life.

There were three dozen or so surfers in the water that day and it took the U.S. Coast Guard 90 minutes to clear the water so the Superferry could dock, according to news reports. Then as the passengers got in their cars and drove off the ramp, they were met by threats from protestors numbering upwards of 250.

People reportedly vandalized their vehicles.

One man tried to let the air out of a car’s tire.

“People who do that, they don’t think they have alternatives. They think that is the only way they get heard,” explains Sue Kanoho, executive director of the Kauai Visitors Bureau.

A picture is perhaps worth a 1,000 words and perhaps nothing could better capture the feeling of Kauai residents being overrun by development, being priced out of buying homes, of their rural lifestyle being devoured by rapid development, than that Honolulu Star-Bulletin photo. Indeed, the photo and event garnered attention throughout the state and beyond. There were national newspaper stories and even the international business magazine, The Economist, ran a story about Kauai’s unrest and the state’s sustainability challenges.

Outside of Kauai, people could not help but ask whether the Garden Island was officially antibusiness? In a series of in-depth interviews, Kauai leaders emphatically stated that’s not the case, it’s far more complex than anything so black and white. “From the outside looking in, you may think that. But the question is, do you know who Kauai really is?” asks Kanoho. “It is a place people protect, cherish and honor.

” It’s also now a place where a heightened state of anxiety about development is changing the way people do business.

In late May of last year, Koloa residents were fuming over the amount of dust drifting off construction sites on Kauai’s south shore. What made the issue so grating was that there were 11 projects in progress simultaneously with eight separate developers involved, according to The Garden Island newspaper. If the perceived transformation of the peaceful community into a resort/luxury-home Mecca wasn’t enough to contend with, there was the dust.

It got so bad the developers formed a group called the Dust Management Hui and launched a hotline for people to call for relief if their homes were hit with a dust wave. The dust hotline goes a long way to illustrate why Kauai residents feel smothered, pun intended, by development. Between cost-of-living struggles and fears of being unable to maintain a rural lifestyle on Kauai, people are frustrated with the prevailing economic forces fueling a building boom in luxury homes and resort properties.

“There are a lot of frustrations that cannot be left unaddressed,” says Joy Miura Koerte, board chair of the Kauai Chamber of Commerce and partner in Fujita & Miura Public Relations. “We need to really take the time to figure out where we are going and how we are going to get there.

”The community unrest with the south shore development is just one of many flashpoints. Just up the road in Koloa Town, there was the monkeypod tree controversy. There, a private landowner’s plan to cut down a stand of aged monkeypod trees brought protests and candlelight vigils and threats to boycott the businesses that would fill the commercial center set to replace the trees. A lawsuit cleared the way for the development this year, but community angst is far from abated.

Another noteworthy hullabaloo was over a plan to build a Super Wal-Mart. The heated debate over whether or not big-box stores were good for Kauai’s business community and the island’s rural character spawned a bill banning big-box stores over 75,000 square feet.

Then, of course, there’s the Superferry.

What lies beneath those controversies is what’s on residents’ minds across the state: housing costs, traffic woes, low-wage jobs and environmental degradation. What makes it so much more poignant is the size of Kauai’s community; everything is more personal. To get a better grasp of the situation, Kauai Planning & Action Alliance (KPAA) produced “Measuring What Really Matters, Community Indicators Report 2006,” a definitive study on resident sentiment and struggles.

(To read the full study, visit http://www.msplinks.com/MDFodHRwOi8vd3d3LmthdWFpbmV0d29yay5vcmc='>www. kauainetwork. org.

) Here is a snapshot of the findings: • From 2000 to 2005, the number of Kauai residents living below the poverty level has increased by 1,000, from 6,031 to 7,078.

• From 2000 to 2005, Kauai median family income has risen by $5,000, from $55,900 to $60,900, an 8.9 percent increase in actual dollars, yet income fell by 6.9 percent in constant (deflated) terms.

• From 2000 to 2005, median incomes on Kauai have risen slightly while median-housing values have jumped sharply, and the affordability index has dropped from 77 percent to 40 percent. That means a family with a median income has only 40 percent of the income needed to afford a median-priced home.

• The number of homeless jumped from 500 in 2002 through 2004 to 700 in 2005.

• Violent crime rose 4 percent from 2000 to 2004, reaching an all-time high of 341 incidents in 2004.

• A total of 5,000 residential units and more than 6,100 resort units are currently pending or will be built within five years.

It’s not surprising that the future of Kauai looks dusty. “There is a heightened awareness of anything that might impact our quality of life,” says Beth Tokioka, director of the Kauai Office of Economic Development. “Processes are not easy on Kauai right now.

” The Kauai 2000 General Plan was to be the noble sword to carve out a bright future for Kauai. “The General Plan has some really beautiful words in it about protecting the rural character of our island and controlling growth and so forth,” says Kauai councilwoman JoAnn Yukimura.

The problem is, Yukimura says, the plan was never really implemented. The General Plan was a testament to what the community wanted to be, but not a true road map to ensure it was achieved.

The real dirty work in planning is not in coming up with the vision, but in making the hard decisions to achieve it, she says. (The same risks also lie in the state’s 2050 plan, she notes.) Because of course everyone wants better schools, high-paying jobs, affordable housing, less traffic, a secure environment. But there is often a trade-off involved. For example, to obtain affordable housing often more building is necessary, which can impact such things as the environment and traffic conditions.

“We want economic development and we want environmental protection and that is put in the plan. But nobody says how we are going to get there,” she says.

Yukimura says instead Kauai often manages growth by reactionary measures such as a laundry list of approval conditions and at times, litigation. “One thousand conditions is not the answer,” she says. “You have to address the issue before it becomes a controversy.

” Kauai Mayor Bryan Baptiste, in a prepared statement, also faulted the General Plan in 2000, in particular for failing to take into account all the developments approved in the 1970s and mid ’80s but not yet built. Those developments in places like the south shore did not break ground until recently, when economic conditions were ideal, and his office, he says, had no control over their approval decades ago.

For his part, Baptiste has undertaken updating district development plans, which also provide constructive platforms for community input. His office has introduced legislative measures to address the issue, including a “Use or Lose It” bill that would require developers to start their projects within five years of approval. Baptiste has also introduced a temporary moratorium on agricultural subdivisions to stem sprawl. Why? According to KPAA, from 2000 to 2005, 1,359 new housing lots were cut out on agriculture land, while 1,600 homes were added in town districts.

“It is my hope that this will stimulate further discussion on how we want to grow, including whether we want agriculture to be a viable industry,” Baptiste wrote to Hawaii Business.

In addition, Baptiste’s administration has a number of smaller programs targeted at such things as agriculture growth. The programs includes reopening the papaya disinfestation plant in Lihue, which, when it closed, virtually knocked out commercial papaya farming on Kauai. He is also working such endeavors as on opening 75 acres in Kilauea to lease affordably to farmers. The difficulty for Kauai, though, is that there is no single silver bullet: Solutions to the various challenges are complicated, require trade-offs and take time, in some cases decades.

More often than not, you just have to bite the bullet.

Energy is a perfect example.

Kauai has the highest power rates in Hawaii. Everyone agrees renewable energies are the future. But what people sometimes don’t realize, says Randy Hee, president and CEO of the Kauai Island Utility Cooperative, is the difficulty in finding the appropriate renewable sources and also ensuring reliability. Hee says many of the renewable energies such as sun and wind require back-up generation because renewable sources are not 24-7 sources. Renewables also require investment, but typically do not provide immediate savings and the KIUC is not eligible for tax incentives because of its nonprofit status.

That does not mean Kauai is not ambitious. Hee says the KIUC has a number of projects in the pipeline and a goal of reducing its greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels and being over 50 percent renewable by 2020. That said, in the current state of affairs, people want to see relief today for their power bills. So do Hee and his board. No one lacks the will, he says.

“The solutions are not quick and they are not easy,” Hee says.

Quietly, while some Kauai residents were screaming at Superferry passengers, rudely receiving Gov. Linda Lingle and even castigating local Superferry supporters, many residents were shamed.

People said vandalizing cars is not how local people act.

People said shouting is not how Kauai people work out issues.

Those comments made in the aftermath of the protests underscored a newly arrived, but marked division on Kauai. Kauai residents often describe the riotous group as the vocal minority, many of them, they say, are new, generally affluent arrivals to Kauai. A common practice is to scan the letters to the editor page in The Garden Island newspaper, not so much for content but for the town in which the letter writer lives, to see whether he or she is new to the island.

Kauai Chamber of Commerce president Randall Francisco acknowledges there is definitely an undercurrent of cultural division contributing to divisiveness.

“I think people felt embarrassed,” Francisco says, referring to the Superferry protests. “We as people of Hawaii and Kauai, most of us came from a plantation community. That multicultural upbringing gives us our identity and sometimes for newcomers, there is a disconnect.

” Francisco continues that, in plantation culture, where everyone was so interdependent, you didn’t always express your opinion so negatively, so publically. “Sometimes how we use language, verbal and nonverbal, is the Red Sea that divides us. I don’t fault newcomers, because they don’t share that experience, but the majority of the community does have that as a reference point.

” That does not mean the silent majority is pro-development. The same fears about overdevelopment and loss of rural character are commonly held throughout the community across all demographics. But longtime residents, who have raised families on Kauai and watched children leave for school and not move back because of a lack of jobs, tend to be more moderate when it comes to development, though just as distressed by traffic woes and even more concerned about cost-of-living issues.

“With a lot of issues, there is a silent majority, made up of a lot of local people, born and raised here. They do have the same interests and they do want to preserve our community our culture, our unique social fabric, but really weren’t against the Superferry and understand why the monkeypod trees have to come out,” says Koerte.

“A lot of the longtime people experience the shutdown of the plantations. They understand something has to come in so there are jobs and their children can return, can come home for work,” she says. “They understand something has to happen for us to progress and compete in a global marketplace. They are people who have experienced downturns.

”Where does that leave business and government?“It’s incumbent upon us to seek out the wants and needs of a large group of stakeholders,” says Tokioka. The challenge though is both cultural and social. When people are working two jobs and struggling to spend time with their families, it is unlikely, even if they were predisposed to speak out, that they would dedicate extra hours to attending council or planning meetings or writing to the newspaper.

Tokioka says a centerpiece of Baptiste’s administration has been providing monthly or bimonthly meetings in communities to seek out a wide representation of community sentiment and also to involve more people in community planning. “The mayor wants to create a dialogue so we can tap into a broader base, to the that greater majority.

” Business, she says, must do the same today on Kauai.

“There is always a concern in business in trying to get something done quickly or efficiently, but I think where we are as an island, it is probably better to take more time and in some cases, a lot more time, and take the input and get buy-in,” Tokioka says. “So you have success at the back-end.

” Is the Superferry a good example of the opposite approach?“Hindsight is always much easier, but clearly that project is not moving forward as planned,” she says. “You really can’t rush things here. It is better to take a little time and do your due diligence and come out with a better product, embraced by a greater segment of the community.

” The same story is taking place on all the Islands. Maui has several flashpoint developments, including Maui Land & Pine’s since tabled plans for Honolua Bay (See our July 2007 issue.) The Big Island has the luxury development Hokulia. On Oahu, there is Turtle Bay Resort; Kakaako Waterfront is another. Communities feel overrun throughout the Islands. Many are also experiencing similar shifting demographics and more diverse stakeholder groups to incorporate.

Early-stage dialogue with communities about development is critical today.

Francisco says the buzzword is triple bottom line, where a business equally values both its own revenues along with the community and the environment. He says while many areas across the state (and country) are debating that formula, on Kauai, the triple bottom line has become mandatory.

“Your business plan has to include community,” he says. “That is what I consistently say in my messaging.

” It was a Monday in March, when Aloha Airlines shut down. Sixty people on Kauai lost their jobs. Sixty people, some with families, lost their income, their health insurance, their security. By Friday, 50 Kauai business owners and executives had gathered for a job fair, to offer them jobs.

“Sixty people, 50 booths, and a ton of pastries. I was like ‘Oh my God! Whoa! Whoa!’” Francisco recounts, his arms raised in mock protest. “We could have opened up a bakery.

” “People just wanted to say we care. We just wanted to let them know, on Kauai, we are one community. No matter what part of the community you are from, we are still Kauai, whether you are for or against the Superferry, for or against runway expansion, whatever. In the end, it is all about Kauai.

” Francisco, like nearly everyone interviewed, points out that Kauai has a extremely high percentage of people who donate money and time to charity, from business executives to blue-collar workers. Indeed, according to the KPAA study, 88 percent of the community donated to community causes. That includes a stunning 68 percent of households making under $25,000.

That’s what Kauai is, he says.

“That is where all of this is leading. People want to be pono. People want to be good. People want to take care of this place,” Francisco says. “Kauai is not antidevelopment. This is a place with tremendous heart and aloha. People want to know you’re genuine, your intentions are good and if the community is taken care of, the business will succeed.

“It is just time to bring everybody together.

”

Comments